- Home

- Brian Turner

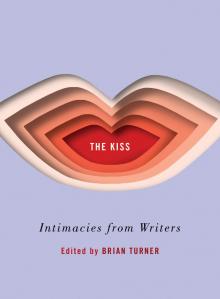

The Kiss

The Kiss Read online

THE KISS

Intimacies from Writers

Edited by BRIAN TURNER

W. W. NORTON & COMPANY

Independent Publishers Since 1923

New York London

That night when you kissed me, I left a poem in your mouth.

You can hear some of the lines every time you breathe out.

—ANDREA GIBSON

CONTENTS

Introduction by Brian Turner

THE LAST KISS by Nick Flynn

NOTES ON THE INVISIBLE KISS by Aimee Nezhukumatathil

THE KISS AT DAWN by Pico Iyer

INTERLUDE by Kim Addonizio

THE KISS I WOULD HAVE SPENT ON YOU by Laure-Anne Bosselaar and Kurt Brown

BAZOOKA SMACKDOWN by Patricia Smith

THE SUMMONS by Mark Doty

THE SECRET KISS by Ilyse Kusnetz

WHERE SCARS RESIDE by Major Jackson

A SYMPHONY IN RAIN by Kazim Ali

KISS, KISS, KISS by Camille T. Dungy

LIGHT YEARS by Rebecca Makkai

KISSING JOE F_______ by Philip Metres

HALF FABLE by Terrance Hayes

THE EVOLUTION OF A KISS by Nickole Brown

KISSING MELISSA by Benjamin Busch

KISS, KISS by Ira Sukrungruang

TRIGGER by Lacy M. Johnson

A LETTER TO MY WIFE ON HER 40TH BIRTHDAY by Brian Castner

FALLING by Andre Dubus III

THE RIDE by Siobhan Fallon

HOLLYWOOD, ENDING. by Schafer John c

A SMALL HARVEST OF KISSES Guy de Maupassant • Marcel Danesi • Diane Ackerman • Roxane Gay • U.S. Army’s Journal for Homeland Defense Civil Support and Security Cooperation in North America • Aimee Bender • Junot Díaz • F. Scott Fitzgerald • J. M. Barrie • Joyce Carol Oates • Jonathan Durrant • Cormac McCarthy • Marlon James • Gabriel García Márquez • George Saunders • Toni Morrison • Markus Zusak • Brad Watson • Hilary Lawson • Steve Martin

KISS KISS BANG BANG by Téa Obreht and Dan Sheehan

CONTAGION by Roxana Robinson

KISS by Honor Moore

GENESIS by Christopher Merrill

A MOTION OF PLEASURE by J. Mae Barizo

KISS, BOUNCE, GRACE by Steven Church

FRUIT by Cameron Dezen Hammon

FIRE THE ANGEL by Martín Espada

LEANING IN by Dinty W. Moore

THE REVOLUTIONARY KISS by Tina Chang

THE HEAVY LOAD by Adam Dalva

MAUDE by Kimiko Hahn

JUDAS KISS by Tom Sleigh

THE SMUGGLER by Ada Limón

A KISS FOR THE DYING by Suzanne Roberts

MAN WITHOUT FEAR by Sholeh Wolpé

WINTER SOLSTICE by Bich Minh Nguyen

THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH by Kristen Radtke

SKEERY THE BLUE by Christian Kiefer

A RECKONING OF KISSES by Beth Ann Fennelly

LATE-NIGHT SESSIONS WITH A BLACK LIBERAL PROGRESSIVE by Christopher Paul Wolfe

AYLAN KURDI, AGE THREE by Matthew Komatsu

BAT VISION by John Mauk

EIN KUSS IM KRIEG by Dave Essinger

THE KISSES WE NEVER GIVE by Kathryn Miles

ON WRITING THE INTIMATE with Nickole Brown, Benjamin Busch, Camille T. Dungy, Pico Iyer, Major Jackson, Philip Metres, and Sholeh Wolpé

Contributors

Everlasting Kisses

INTRODUCTION

Brian Turner

From Sioux Falls to Santiago to Paris, from Tehran to Khartoum to Reykjavík, Kyoto to Darwin; from the panchayat forests of India to the Giant’s Causeway on the coast of Northern Ireland; in taxis and at bus stops and in kitchens and in sleigh beds and in haystacks and at airports around the globe people are kissing one another. This is not the scripted passion of Hollywood. The kissing that takes place in our lives is far more complicated and messy and human than the celluloid veneer of the silver screen. The kissing doesn’t stop when the bombings take place in Aleppo, Madrid, Paris, or London. It doesn’t stop when members of Pussy Riot are beaten and thrown in prison. It doesn’t stop to consider Banksy’s latest offering on the politics of art. It doesn’t stop when Christo and Jeanne-Claude wrap the Reichstag in fabric and even when Christo says that it takes “greater courage to create things to be gone than to create things that will remain.” The grandmother blowing kisses to her loved ones who are reduced to tiny images on an iPad, the eleven-foot-tall man leaning over to kiss the blaze of a horse’s forehead, the distant fathers, the deported mothers, the generations of children—they are all filled with kisses as necessary as rain. And yet. The great and recorded moments of history mostly elide the profound moments, like the kiss, that comprise the very essence of our individual lives.

There are variations of the kiss that we need to explore and learn from. The ineffable kiss transported into language. The sublime kiss. The ambiguous kiss. The devastating kiss. The kiss we can’t take back. The kiss we can never give. The broken kiss. The lost kiss. The kiss that changes a life.

One of the most memorable kisses I’ve ever witnessed took place at a Muay Thai fight during a ten-bout championship night at the Lumpinee Boxing Stadium in Bangkok, Thailand. The main event featured a young up-and-coming fighter facing off against the old champion. Tickets in hand, my wife and I sat ringside, eating sticky rice packed in bamboo containers and drinking Singha. A traditional musical trio—a hand drummer, a string player, and a wooden flutist—improvised music to match the intensity of the fight. The fight itself lived up to its billing as a pairing of two masters of the craft. And yet, what intrigued me most, stunned me, really, was what happened immediately after the young fighter kicked the old champion in the head, laying him out cold on the canvas. Initially, and predictably, the young fighter ran barefoot to his own corner, near us, and leapt up to stand on the first set of ropes, his gloved hands lifted upward in victory while a cheering of flashbulbs covered his body in light. At this moment, at the apex of his success, his knuckles and feet still stinging with the win, the young champion now crossed the ring to kneel before the old champion he’d just dethroned. The beaten man sat on a stool now, a cool towel draped over his head, aided by members of his team beside him. With the world looking on, the young champion bent over and kissed the tops of the other man’s feet. An astonishing act of reverence. I’ve never seen anything else like it.

And yet. I typed the last paragraph while sitting on the eighth floor of a cancer ward while my wife received two whole units of hemoglobin, a dose of steroids given as a precautionary measure to reduce the swelling in her brain, and a series of other drugs. We heard a harp playing a few rooms down, and soon learned a wedding was under way. The bride was still in her twenties, and in my mind’s eye I pictured the family gathered around the bed, a photographer in the back, everyone in their finest, some with tissues in their hands, the priest leading the ceremony. Such a fierce and soon-to-vanish thing—love. The bride’s mother reaches over to gently moisten her daughter’s lips with a cool swab, brushes her hair back from her forehead, and rearranges her daughter’s opened veil. In Spanish, the priest says, “You may now kiss the bride,” and the young man leans over to kiss his wife. And she doesn’t close her eyes at first. She wants to see it all. To take everything in before the tears overwhelm her and, as weak as she is, to raise her arm and touch the side of his face as they kiss.

It’s like this the world over. Some kiss a trophy and hoist it high over their heads. Some kiss the Blarney Stone. Some kiss the very ground at their feet.

As you read this, a teenager practices kissing a mirror, imagining that first-ever kiss with S from fifth-period science class, her eyes open until the moment lips touch their own cool reflection, an inexact gesture toward transcendence, the violin rehearsing for i

ts duet, testing the limits of the soul within the human frame, learning to shape the notes that rise over the music and then disappear.

A man in his seventies leans over the railing of a hospital bed to kiss his younger brother on the forehead—once the respirator has been switched off, the EKG flatlined into a digital silence—while those gathered around the bed have turned to hold one another, some of them sobbing, one of them considering how tender the kiss is and how the arc of two lives over decades of moments has condensed into this one sweet gesture, though the cooling body of the dead can offer no gesture in return.

A soldier, soon to return to war after a few days on leave, lies in bed with a woman whose last name he doesn’t know, the word muerto tattooed on her inner thigh. He wants to wake her and also wants her to continue sleeping forever with her head on his chest, knowing that when she wakes she will kiss him and that it could be the last kiss of his life. And yet, when she wakes, he will kiss her as if it isn’t the last one ever, as if it’s just a kiss between brief lovers, a small hunger of the body and not a portion of the soul saying goodbye to a world near the end of its days.

There’s a mother in the county jail, kissing her nine-year-old through the bulletproof glass in one of the visitor booths, the child angry and crying and sullen and saying, “I love you, too,” as the bored deputy on duty pauses a moment to let them kiss a while longer like this before tapping the microphone and saying—as the mother motions with her hand as if smoothing the child’s hair away from her eyes, the way she sometimes did early in the morning or when putting her child to bed—“Time’s up. Time’s up.”

And the USS Oak Hill has docked in Virginia, with Petty Officer Second Class Marissa Gaeta getting the coveted “first kiss” on the dock with her girlfriend, Petty Officer Third Class Citlalic Snell. It’s a kiss worthy of a postcard, a lean-back movie star kiss with two brunettes kissing until the world around them diminishes and sloughs away. This isn’t a 1940s kiss. This is an eighty-days-at-sea kiss. This is the longed-for kiss, the I’ve-thought-of-this-moment-every-night-since-I-last-saw-you kiss. A kiss of solitude. A kiss of absence. Something made of starlight over a moonless ocean. A kiss to mark the sailor’s return.

And there’s a couple making love in a Mosul park, not far from the Tigris River, pausing to look each other in the eye for longer than they’ve ever done before, the sound of a pickup truck rolling not too far off through the eucalyptus grove, an explosion in the distance, as they continue to kiss now, though shifting somehow in response to the world and the cruel weight of time itself, to kiss soft and slow, kissing truly for the first time, a kiss that erases the kisses they’ve shared before, or maybe simply changes the nature of their kissing forever on from this point—now that they’ve slowed themselves long enough to really see one another, and as they imbue the word love with an altogether new layer of meaning.

For this anthology, I’ve invited writers and thinkers to share their thoughts on a specific kiss: an unexpected kiss, an unforgettable kiss, a kiss to circle back to. My intent here is to focus on kisses that—at least in some sense—attempt to bridge the gulf, to connect us to one another on a deeply human level, and, as closely as possible, to explore the altogether messy and complicated intimacies that exist in our actual lives, as well as in the complicated landscape of the imagination.

THE KISS

El mundo nace cuando dos se besan.

The world is born when two people kiss.

—OCTAVIO PAZ

THE LAST KISS

Nick Flynn

The Queen, asleep in the forest, her body laid out on a stone slab. Moonlight on her cheek, the blanket that covers her is blood-red. A willow weaves a mottled canopy of dark above her.

This, like many fairy tales, centers on a kiss.

If the Prince finds her in time he can wake her, but he is unsure which path to take—maybe the ravens have (once again) eaten all the breadcrumbs. If he gets there too late then she will never wake up.

The moral, if there is one, is that there really is no way to know when something—anything—that you do everyday, or even something you’ve done only once, will turn out to be the last time. The cup you drink your coffee from each morning—your favorite cup—is already broken. If you can think of the cup this way then you will, perhaps, hold onto it more tightly. Perhaps you will appreciate each moment you still have with it until it does, finally, forever, break.

Everything is already broken.

The kiss that comes to mind, if asked, is the last kiss I gave my mother—it rises up, unbidden. It’s dusk, she’s upstairs, lying in her bed, coming out of—or going into—another migraine. It’s just after Thanksgiving, I’ve come home for a few days for the holiday. I’m living outside of the house by now, finishing up my junior year at college. My mother is still young—forty-two, still beautiful, still desired—young enough to start over. Her boyfriend’s been in jail for a couple years now (he got caught smuggling drugs). He’s up for parole in a month, but while he’s been away she’s been seeing someone else. I’ve been out with friends, likely getting high in our cars in the Peggotty Beach parking lot—these days I am always getting high. I’m home now to say goodbye, to let her know I’m about to get on my motorcycle and push on, ride back up to school. I climb the stairs to her bedroom. The lights are off, a tiny orange bottle of white pills within reach. Her eyes are closed, her blanket is red, her skin alabaster—maybe she’s a little high herself, or a little hungover. The Queen is in pain, maybe mortal pain. If she doesn’t open her eyes she might never open them, the Prince knows this, he’s been wandering this forest his whole life, the breadcrumbs all eaten. The Prince leans over her face, as he had done so many times, to whisper the words that will keep her there, only the words don’t come, or they come out wrong. Can I get you anything? The voice coming out of him (see you soon) doesn’t even sound like him. Kiss her, it murmurs & so he does & her eyes open & the spell, for that brief moment, is broken.

NOTES ON THE INVISIBLE KISS

Aimee Nezhukumatathil

Through wing, through vein and brittle wrist bone, how I kissed and moved with you still remain. After all this time you’d think I’d forget—already the sounds of a lost coin or click of a locket clasp I can’t recall, the first notes of an ice-cream truck on your street: gone. There’s a place in Lake Superior where butterflies veer sharply when they fly over a particular spot. No one could figure why such a change, such a quick turn at that specific place—until a geologist made the connection: a mountain once rose out of the water in that exact location thousands of years ago.

These butterflies and their butterfly offspring can still remember a mass they’ve never seen. Can remember sound waves breaking just so and fly out of the way. How did they pass on this knowledge of the invisible? Perhaps this message transmits in the song they sing themselves on their first wild night, spinning inside each chrysalis. Or from the music kissed down their backs as they cracked themselves open in the sun. Did milkweed whisper instructions to them as it scattered in the meadow?

And maybe that is the loneliest kind of memory: to be forever altered by an invisible kiss—something long gone and crumbled. Maybe that explains why, in the distant future, a gorgeous sound will still wound even my great-great-great-great-great-grandchild—a sound she can’t quite place, can’t quite name. That sound will prick at her and prick at her. And that sap-sticky pine needle will be a chalky kiss smudging her hands with a pale color found only in the crepuscular hour of the day.

An invisible kiss is like that: what you remember won’t come from a single script or scene, but from, say, the surprise of purple quartz inside a geode. The first time I smashed one, I put it inside a sock so any shards wouldn’t slice into the dark iris of my eye. And after the first careful taps, I clobbered it, already trying to prepare myself for disappointment: a sock full of crumble. But when I slid out the pieces into my palm, I couldn’t believe my luck—the violet-rich sparkle!—and suddenly I was back

in ninth-grade science class and timed quizzes to identify minerals on the Moh’s scale of hardness.

Everyone knew talc was the softest on the scale and everyone of course knew diamond. Hardly anyone remembered the minerals in between. But I was always drawn to quartz—I lingered over it the longest, flipped it over in my hand, even tasted it when no one was looking: like campfire smoke left in a shirt.

Once, when I vacationed in the Keys, I scattered my pastel treasures from the beach—coquina shells—on a windowsill before bedtime. I did not know they were still alive. When I woke, the tiny clams had sighed open, their tongues evaporated during the night. Who knows how many invisible kisses covered me while I slept?

THE KISS AT DAWN

Pico Iyer

I steal out of my little room with the first call to prayer, and take a taxi through the darkness to the central souk. The stores are shuttered now, but the thronged smell of spices and bodies is everywhere, overwhelming. I walk past the great mosque, a center of the Islamic world since the eighth century, and along the thin alleyways that fork this way and that through the Old City of Damascus. Then, as every morning, I arrive at the marble floor that leads to the golden shrine.

A little door admits me to a space as brightly lit as a nightclub, where a young man, black-suited and rosy-cheeked, is singing of the love that’s recently deserted him. Bodies are everywhere, hunched over, shoulders sagging, faces turned up now and then so I can see the tears glistening, running down their cheeks.

At the center of the space an old man is kissing, kissing a bejeweled grille as if saying goodbye to the woman he’d loved for sixty years and now will never see again.

I watch him, rapt, as pieces of colored glass in the windows send exploding reflections all around, and see him turn away, red-eyed and shaking. An old woman now is kissing around the same area, and she might be kissing the son she’s sending off to war.

The Kiss

The Kiss